Cosmas Indicopleustes and his Amazing Throne

July 29th, 2025

Some time in the sixth century CE, an anonymous merchant-turned-monk (who credits himself only as "A Christian") wrote a book called the Christian Topography. This merchant, given the name Cosmas Indicopleustes (from Greek Kosmos for "the universe" and a phrase meaning "sailor to India"), had some rather idiosyncratic ideas about the world. In a Greek-speaking world that by that point had known the Earth was round since Erastothenes had calculated its circumference from the differences in lengths of shadows at different points along the Nile some 700 years before, Cosmas put forward the bold idea that the Earth is actually flat and that the heavens form a box-like shape with a curved lid around said flat Earth, in imitation of the shape of the tabernacle in the Old Testament. Needless to say, Cosmas's ideas were not especially popular in the Byzantine world (likely his Nestorian Christianity, which would have been considered well and truly heretical by the Roman mainstream, didn't help there), but thankfully for us, the controversy that his flat Earth cosmology inspired (and the universal fascination that medieval Greeks had for all things distant and foreign, which Cosmas referred to extensively to build up his argument) meant that generations of eastern Roman scribes continued to copy his Topography, and it is these copies of copies that mean we even have the work at all today.

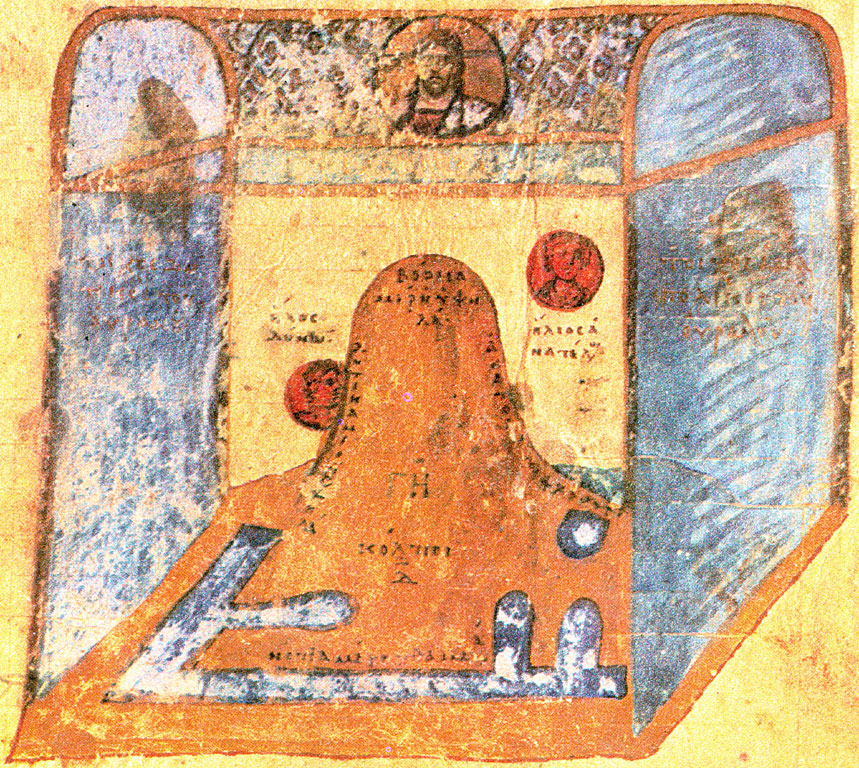

A visual representation of Cosmas' cosmology

Why am I bringing up Cosmas Indicopleustes' best attempt to justify seeing the whole universe as a big tent? Well, because the Christian Topography is the only record that we have of an artifact that serves as a really fascinating look into the history of the Horn of Africa (one of my favorite parts of the world to delve into the history of) in antiquity! And, the fact that we only know about this artifact from copies of copies of a cosmological treatise that people didn't even particularly agree with all that much is just so fascinating to me. To get the citation out of the way, this post is referring in its entirety to the book The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam by G.W. Bowersock; I'm not going to be reproducing the entirety of that book's contents here, of course, and I'd really recommend that you read it! It's very engagingly written and serves as a fantastic introduction to a time and a place that doesn't get nearly the historical attention from general readers that it deserves. I actually read the book itself a few months back and proceeded to procrastinate on writing this scrap about it, since I'm just the absolute worst at not procrastinating on things. But anyway, please do check Bowersock's book out, it's great!

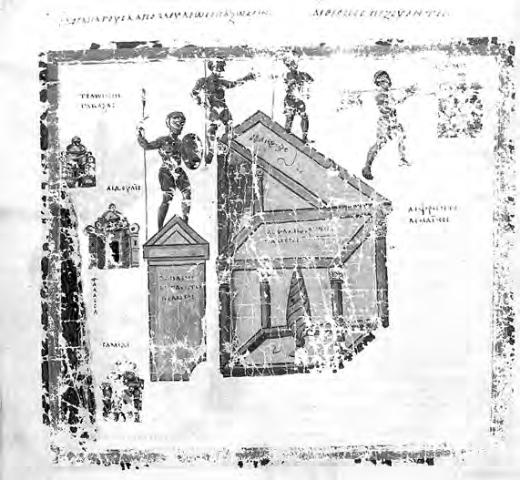

A map of Adulis with the monument highlighted, from one of the manuscripts of the Christian Topography; south is on the top, so Aksum, which is south of Adulis, appears above it here!

In Book 2 of his Christian Topography, Cosmas Indicopleustes recounts a story from his travels in the part of "inner India" that formed the Ethiopian kingdom of Aksum, today part of the state of Eritrea. While in the city of Adulis, on the Gulf of Zula, Cosmas and another merchant (who would later also become a monk) were given a mission by the local governor of the province. You see, the negus of Aksum, the king of the kingdom which ruled over Adulis, found out about an ancient monument (later termed the "Monumentum Adulitanum") with an inscription on it in the vicinity of the city and wanted it transcribed for his reference. So this request trickled on down from the negus to the governor and down to Cosmas, who not only wrote down what was written on the monument but also wrote a physical description of it and kept extra copies of his transcription and description for himself. And we all have his fastidiousness there to thank, because the monument is now lost! While many stelae with various inscriptions or lack thereof have been found across the former territory of the kingdom of Aksum, the precise monument described by Cosmas has never been rediscovered, and we only know about it because a monk with a bit of an ax to grind thought bringing up the anecdote would further his argument for the flat Earth. I'm sorry for reiterating that a few times, but I just find that coincidence, that confluence of totally unrelated factors giving us this peek into history that we otherwise wouldn't have, just amazing.

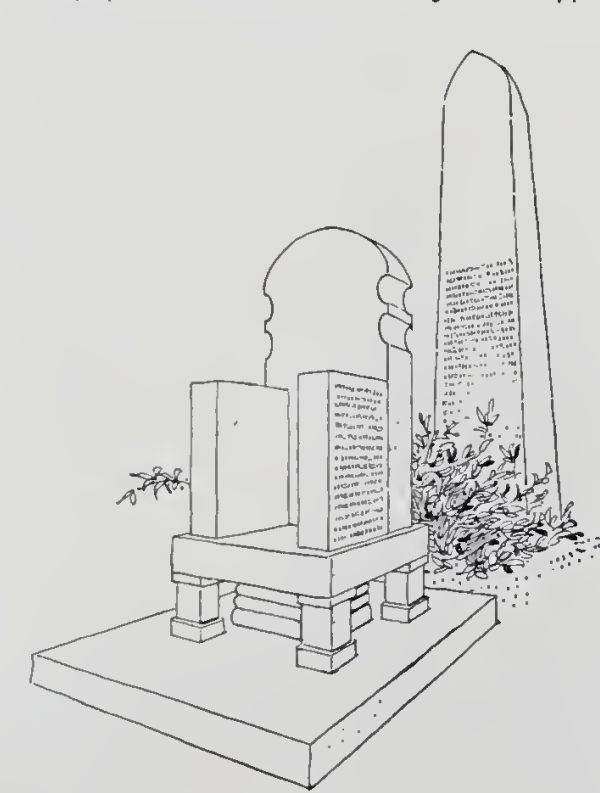

So, the monument. More accurately a throne, according to Cosmas' description it was made entirely of marble (he notes not marble from the Greek island of Proconnesus), with a low seat set upon four short columns with a larger central pillar under the center of it. A tall back and arms completed the structure, the whole thing was carved from one block a little over 3 feet tall, and on the arms of the throne there was a Greek-language inscription. Stone thrones like this one were a common enough monument in Aksum, likely votive in nature, and archaeologists have unearthed enough other examples to be able to say that the construction as Cosmas describes it is pretty typical other than the short columnns holding it up. Behind the marble throne sat a taller stele carved from black basalt with a triangular top ("like the letter lambda") and another inscription in Greek about halfway up the stele's height. Cosmas took note of the two inscriptions and (wrongfully) believed them to be the same singular narrative, starting on the basalt stele before continuing on the arm of the throne (making this assumption more or less just because the inscription on the stele breaks off after a certain point). In reality, however, there was a gap of centuries between the two inscriptions, with the one on the basalt stele being much, much older.

The inscription on the basalt stele was dedicated by the Hellenistic-era king of Egypt Ptolemy III, the third pharaoh of the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled over Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great. Ptolemaios Euergetes, "Ptolemy the Benefactor," ruled Egypt from circa 280 BCE to 222 BCE, a full 700, almost 800 years before Cosmas visited Adulis. Adulis, all the way down the African Red Sea coast, was likely well outside of the territory that king Ptolemy actually could control, but it seems that he made a trip down to the edge of what he would have understood as the known world to exert even a little bit of control and secure access to elephants that he could use in his wars with the rival diadochi, the successors of Alexander. And so, after a jaunt down the African coast hunting for elephants, Ptolemy III seems to have come upon Adulis and decided to order a monument to his exploits erected there. And on that moment, he had written:

Great King Ptolemy, son of King Ptolemy and Queen Arsinoe, who are brother and sister gods, themselves the children of King Ptolemy and Queen Berenice, who are savior gods, a descendant on his father's side from Heracles, son of Zeus, and on his mother's side from Dionysus, son of Zeus, having assumed from his father a royal dominion of Egypt, Libya, Syria, Phoenicia, Cyprus, Lycia, Caria, and the Cyclades islands, led an expedition into Asia with a force of infantry, cavalry, a fleet of ships, and elephants from Troglodytis and Ethiopia. These animals his father and he himself first hunted out from these places and brought to Egypt for use in war. Having become master of all the land west of the Euphrates--Cilicia, Pamphylia, Ionia, the Hellespont, Thrace, and of all the armed forces in those lands as well as Indian elephants, and having brought the monarchs in all those places into subjection to him, he crossed the Euphrates river and subdued Mesopotamia, Babylonia, Susiana, Persis, Media, and all the remaining territory as far as Bactriana. He recovered all the holy objects that had been carried away from Egypt by the Persians, and he carried them back to Egypt with the rest of the treasure from the region. He sent his forces by way of canals that had been dug...

Ptolemy III very much did not conquer most of the places he claims to have conquered here. If he had actually pulled that off, he'd basically have been Alexander 2! But, perhaps he thought that all the way out in Adulis, nobody would really be able to fact check him on that. That the east African coast was a hub for elephant hunting and elephant trading is a more uh... confirmable detail, and one that's actually pretty notable given how early this is! The later Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written in Roman Egypt sometime in the 1st century CE, describes elephant trade in this region (and is in general our only look into east Africa at that time, at least in terms of written sources), but this is 200 years earlier than that! So, Greeks, Macedonians, and Romans coming down from Egypt took an interest in this stretch of coastline for its elephants, sure, but what did the people from east Africa find valuable about Adulis? Well, thankfully, someone else came upon this basalt stele several centuries after Ptolemy III died and took some inspiration from the account of his exploits and decided to make a votive throne with an inscription of his own.

In the 3rd century CE, an obscure Aksumite king known only from south Arabian inscriptions (where his name is rendered GDRT--ancient south Arabian, like modern Arabic without the diacritic markers, didn't write vowels!) and (possibly) from Cosmas' throne (if the king who made the throne inscription is the same king) embarked on a series of military expeditions against his neighbors in Africa and across the Red Sea in Arabia. Unfortunately, the opening lines of his inscription commemorating these military victories was seemingly already lost by the time Cosmas got there. But, the inscription (written in Greek, which indicates how closely connected Aksum was to the Greek-speaking world even before converting to Christianity down the line) provides a glimpse of east African culture, religion, and politics in a time where we have very, very few other written documents:

...afterwards I grew to manhood and bade the nations closest to my kingdom to keep peace. I waged war and subjugated in battle the following peoples.

I fought the tribe of Gaze, then won victories over the Agame and Siguene. I took as my share half their property and their population. The Aua, Zingabene, Aggabe, Tiamaa, Athagaoi, Kalaa, and Samene, people who live beyond the Nile in inaccessible and snowy mountains, in which there are storms, and ice and snow so deep that a man sinks in up to his knees--these people I subjugated after crossing the river. Then I subjugated the inhabitants of Lasine, Zaa, and Gabala who live by a mountain with bubbling and flowing streams of hot waters. I subjugated the Atalmo and Beja and all the peoples of the Tangaitai with them, who dwell as far as the frontiers of Egypt. I made passable the road from the places of my kingdom all the way to Egypt. Then I subdued the inhabitants of Annene and Metine on craggy mountains.

I fought the Sesea people, who had gone up onto the greatest and most inaccessible mountain. I surrounded them and brought them down, and I chose for myself their young men, women, boys, girls, and all their property. I subjugated the peoples of Rauso who live in the midst of incense-gathering Barbarians between great waterless plains, and I subjugated the people of Solate, whom I ordered to guard the coasts of the sea. All these people, enclosed by mighty mountains, I myself conquered in person in battle and brought them under my rule. I allowed them the use of all their lands in return for the payment of tribute. Many other peoples voluntarily subjected themselves to me by paying tribute.

I sent both a fleet and an army of infantry the Arabitai and the Kinaidocolpitai who dwell across the Red Sea, and I brought their kings under my rule. I commanded them to pay tax on their land and to travel in peace by land and sea. I made war from Leuke Kome to the lands of the Sabaeans.

I was the first and only king of any down to my time to subjugate all these peoples. That is why I express my gratitude to my greatest god, Ares, who also begat me, through whom I brought under my sway all the peoples who are adjacent to my land, on the east as far as the Land of Incense and on the west as far as the places of Ethiopia and Sasou. Some I went and conquered in person, others by dispatching expeditions. Having imposed peace on the entire world under me, I went down to Adulis to sacrifice to Zeus, to Ares, and to Poseidon on behalf of those who go under sail. Once I had brought together my forces and united them, I encamped in this place and made this throne as a dedication to Ares in the 27th year of my reign.

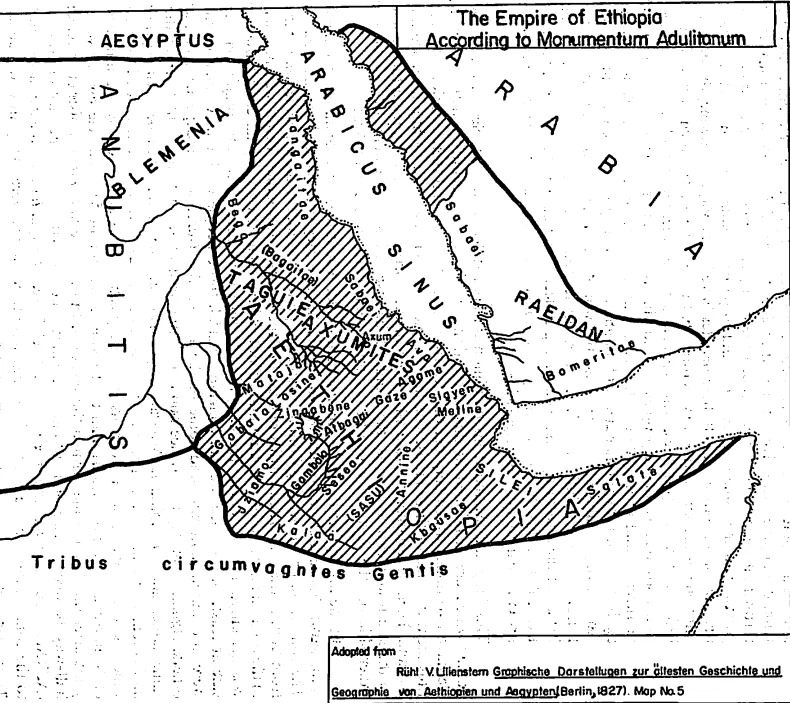

A map of what the extent of GDRT's empire may have been

Most of the people groups mentioned in that first paragraph there are incredibly obscure, like there's some suggestions as to who some of them are (Samene looks very much like the Simien mountains, which were later the epicenter of a Jewish kingdom, etc.), but for the most part we don't really know the historical identities of most of those tribes and nations GDRT conquered. What we do know the identity of are the Arabitai (Arabs!) and the Sabaeans, both peoples of the Arabian peninsula (clearly, I mean, he says they dwell across the Red Sea). GDRT's conquests were the first but by no means the last time that an Aksumite king would conquer across the Red Sea and carve out an area of control in Arabia!

In fact, the negus who gave the local governor the mission (which the governor then handed off to Cosmas) to retrieve a transcription of the inscription at Adulis was, more likely than not, the Aksumite king who went on to follow up his predecessor's conquests with a military campaign into Arabia of his own! Not too long after Cosmas would have been in east Africa, the Aksumite king Kaleb (also known as Elesbaan) began a campaign against the Jewish Yemeni kingdom of Himyar, whose king Yusuf Dhu Nuwas was persecuting Christians under his rule (by this point, Aksum had been Christian for about a century). We're getting into speculation some here, but maybe Kaleb was planning that war and, knowing there was a record of his predecessors exploits at the monument in Adulis, requested a copy for his own reference while he planned the campaign?

Anyway, that conflict is actually what makes up the bulk of Bowersock's book, and it is well beyond the scope of recounting an interesting little historical/archaeological tidbit to you all; go read The Throne of Adulis if this has piqued your curiosity! That's more or less all I wanted to share for now; I really do recommend the book to you all, it's a great read! Late antiquity is absolutely fascinating, and the ancient and medieval history of Africa doesn't get nearly the attention it deserves, so please read more about it!